Global biodiversity loss has reached a point of crisis. A now well-understood set of drivers, combined with positive feedback loops, has caused what is being termed the 6th mass extinction in a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. Although much media focus has been on recognised global biodiversity hotspots and their degradation, the biodiversity of Ireland is no different in experiencing the same suite of pressures, including habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, population pressure and the over-harvesting of renewable natural resources. According to most recent assessments, 86% of habitats in Ireland are in ‘unfavourable’ condition, while the list of endangered Red-listed birds increases at each assessment. The 3rd National Biodiversity Action Plan (2017-2021) aims to remedy this through targeted actions and strategic objectives. Concurrently, Ireland will struggle to meet its commitments to reduce carbon emissions. Addressing these challenges is further constrained by grossly inadequate funding.

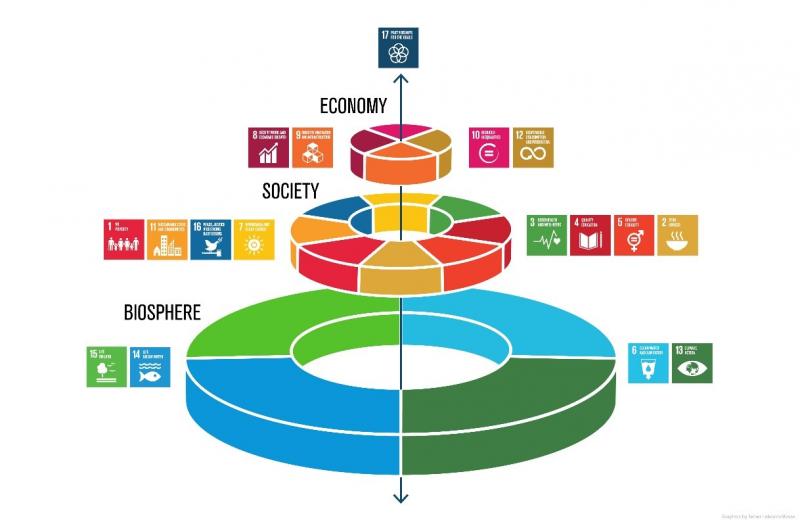

We know the measures required to address these challenges, yet action continues to be limited. In much the same way that climate action is now a socio-political endeavour, action to stem the loss of Irish biodiversity is increasingly seen through a socio-ecological or socio-economic lens: engaging with people, encouraging positive behavioural change, promoting science-based policy design and mainstreaming biodiversity concerns across multiple sectors, noting especially the fundamental importance of well-functioning ecosystems to human development set out in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (figure 1).

Figure 1: The UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, showing the reliance on all other goals on those constituting the biosphere.

The impetus to act is lacking, despite overwhelming evidence that we have little long-term choice for our own well-being. Voluntary engagement remains largely limited to the “usual suspects”, a point highlighted by Connecting Nature in the past (see: Engaging the UN-Usual Suspects). Instigating behaviour change and action amongst the “un-usual suspects” is often reduced to a cost-based decision: i.e. although I may care about the loss of biodiversity, what are the benefits to me and what cost or inconvenience will I need to accept to change my land management practices, attitudes to consumption, energy generation or lifestyle choices?

Thus, one of the largest challenges to achieving tangible, targeted biodiversity conservation goals is establishing a sustainable financial framework which equitably shares the burden of conserving biodiversity as cost-effectively as possible. While presuming that no major shift in the current global neo-liberal economic model is imminent, effort must foremost be dedicated to better allocating the resources at our disposal, identifying new financial mechanisms, or revealing and strengthening synergies between cross-sectoral agendas to realise the co-benefits of biodiversity in relation to climate action, sustainable development and economic prosperity.

The Biodiversity Finance Ireland project is one such project addressing the challenge of biodiversity finance, specifically in an Irish context. Based in the Planning and Environmental Policy Research Unit of University College Dublin and funded by the Irish Research Council and the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), this project adopts an existing United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) BIOFIN model to use the wealth of knowledge and experience of the developing world in coping with the acute pressures of climate change and biodiversity loss. In total, 31 developing nations have already undertaken a BIOFIN approach to biodiversity preservation and restoration. These previous BIOFIN assessments benefit from a growing suite of financial mechanisms to fund existing and novel conservation initiatives, or through the mainstreaming of biodiversity concerns into broader policy and institutional discourse.

The aim of Biodiversity Finance Ireland is to 1) characterise the gap between current resources and those needed to conserve biodiversity, 2) identify potential synergies and co-benefits in meeting biodiversity and climate targets, and 3) highlight harmful subsidies that threaten these across various sectors. This is the first time a developed nation has used the BIOFIN model to strategically plan the financial needs of conserving national biodiversity.

To date, the research project has produce two outputs; a National Biodiversity Expenditure Review (NBER) and a Policy and Institutional Review (PIR). The NBER examines existing expenditure and its contribution to Ireland’s international and national commitments, recording biodiversity spending by government departments, agencies and NGOs between 2010 and 2015 and comparing these with the objectives and targets of Ireland’s National Biodiversity Action Plan 2017-2021 and the CBD Aichi Biodiversity targets. The PIR presents the initial stages in developing a holistic view of the fiscal, economic, legal, policy and institutional frameworks of the larger BIOFIN assessment. It provides an overview of the institutional and policy landscape which is driving biodiversity loss at a national level and of the existing finance mechanisms in place, including subsidies and sources of revenue.

Two key deliverables then remain, presenting actionable recommendations and a data-driven roadmap for change. Having assessed the levels of expenditure in the NBER, and the functioning of relevant policies and institutions in the PIR, a Financial Needs Assessment (FNA) will ascertain the levels of finance required to (at minimum) meet our national biodiversity conservation targets. The FNA will reveal the funding gap that must be filled if we are to meet our national and international biodiversity commitments and the institutions involved in delivering biodiversity actions. This will inform a Strategic Financial Plan (SFP) which will present a roadmap to achieve improvements in efficiencies or expenditure allocation and highlight sources from which new funding can be secured.

Under the context of rising global urbanisation, and the increasing density of conurbations, urban biodiversity will be key to myriad ecosystem services and nature-based solutions, not least towards human health and wellbeing, or the salutogenic benefits of nature. In Dublin, Bull Island is a multi-faceted representation of these potential benefits, an anthropogenic sandbar straddling the side of Dublin Bay, itself a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. As an SAC and SPA, Bull Island is vitally important for species and habitats included in the EU’s Birds and Habitats Directives, but is also an increasingly valuable amenity for the citizens of the northern Dublin suburbs. Additional to these benefits, Bull Island has always played a role in protecting the north city from storms and could now play a critical role in mitigating the effects of climate-driven coastal erosion and sea-level rise through its extensive dune and mudflat ecosystems (figure 2).

Figure 2: Bull Island, Dublin Bay. Generated by the construction of the North Bull Wall (left), this sand bar and associated saltwater mudflats provides numerous ecosystem services, while being a haven for biodiversity.

The value of Bull Island, as a single example, to wildlife, amenity and protection from climate change is clear. Estimating the costs of protecting such a valuable nature-based solution are therefore critical if a pragmatic economic argument is to be made for its protection. Similarly, identifying the best sources of financing and carefully strategizing its spending will be an increasing imperative to retain these natural defences in the face of climate-driven uncertainty, while allowing nature to provide its broad range of valued ecosystem services. The Biodiversity Finance research project intends to do exactly this, using a tested model already in use by the most vulnerable societies on earth, those already acutely aware of the impacts of biodiversity loss.

Dr Shane Mc Guinness and Dr Craig Bullock

Further information on this research project can be found at https://biodiversityfinance.ucd.ie/